Reading and Language Arts Foundations of Language Develop and Emergent Literacy

Information technology is important to facilitate children'south enjoyment and love for reading and writing.

This teaching practice expands upon the practices: reading with children and writing with children.

This section covers additional theories and pedagogical strategies to develop children'due south contained engagement with texts focussing on emergent readers and writers.

The benefits of contained reading and writing

Creating time and space for independent exploration and creation of texts allows children to experiment with emergent reading and writing behaviours without adult support.

Independent reading and writing can assistance develop children's sense of ownership over their skills and provide some quiet time where children tin work and explore uninterrupted, at their own pace.

The importance of children's contained exploration and creation of texts is supported by the Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (VEYLDF, 2016):

They become aware of the relationships between oral and visual representations, and recognise patterns and relationships. They learn to recognise how sounds are represented alphabetically and identify some letter sounds, symbols, characters and signs. - VEYLDF (2016)

Immature children brainstorm to explore written communication by scribbling, drawing and producing approximations of writing… They create and display their own information in a way that suits different audiences and purposes. - VEYLDF (2016)

Independent reading pedagogies

As described in the reading with children section, while reading together, children and adults engage in different reading behaviours (as per the gradual release of responsibility model: Duke and Pearson, 2002.

Independent reading requires very little or no educator support, and involves the following:

- children appoint with texts independently without assistance from educators

- educators may notice children during independent reading or leave them to read by themselves

In early childhood, where children are unlikely to be "reading" texts (correctly decoding many/most words) on their own, these independent literacy experiences are nonetheless important for assuasive children to explore and enjoy mimicking the reading process at their ain pace. Children can:

- bespeak out pictures and favourite parts

- recite familiar parts

- revisit familiar stories and concepts and find parts they similar the almost

- start to recognise short words from repeated readings with adults

- mind to audiobook versions at the same fourth dimension as reading through the text

- relish the reading process for an extended menses of time.

Encouraging contained reading

It is important to create multiple opportunities for children to independently appoint in reading experiences, based on their interests, and at their own pace. The following main strategies tin can assist to encourage children's independent reading in early babyhood settings.

Reading and book corner spaces

- setting up dedicated reading spaces that are comfortable and appealing for independent exploration of texts, too as shared reading with peers

See Literacy-rich environment for more information.

Audiobooks

- educators can source audiobook versions of familiar texts to provide multisensory independent reading experiences

- by providing headphones (with volume controls to prevent hearing damage), children tin apply audiobook versions to enhance their independent engagement with books.

Providing books for independent reading

Information technology is helpful to provide books and other texts in which children take shown an interest. Children may as well cull books that are unfamiliar or new, but it is also desirable to make bachelor the texts that take already been explored during modelled and shared/guided reading experiences.

As with all emergent reading experiences, it is of import to cull a book that:

- matches the age and linguistic communication skills of the children

- includes characters, events, and letters within the story that will appeal to children

- is the right length for the learning experience

- highlights aspects of oral language and emergent literacy that can exist explored with children or they can practice independently (including making meaning, vocabulary, concepts, phonological awareness, fine motor, text structure and features).

See an overview of types of children's literature (including ICT texts) in the learning focus Exploring and Creating Texts.

Independent writing

Independent writing pedagogies

As discussed in the writing with children section, during contained writing experiences, children and adults engage in dissimilar reading behaviours (as per the gradual release of responsibility of model: Duke and Pearson, 2002; Fisher and Frey, 2013; Pearson & Gallagher, 1983).

Independent writing requires:

- educators to provide space, materials, and writing stimuli

- children to create their own texts from beginning to end, drawing upon skills and cognition gained in other emergent literacy experiences

- educators to enquire children about their drawings/writings, and add any annotations if the child directs them to

- educators to provide back up or scaffolding as needs arise, but children are most entirely independent.

It is expected that children volition use a combination of marking making, scribbling and drawing as their earliest forms of written expression.

Some children will also experiment and brainstorm to employ aspects of print in their writing, though it is non required that children use print elements in early childhood settings.

Encouraging independent writing

Through independent writing, children can develop their skills in their ain time, and driven past their own writing interests (for case: making meaning and expressing ideas through texts, concepts of impress, phonological sensation, early phonics, exploring and creating texts).

Writing areas

Educators can set up upwardly these areas for contained exploration of drawing/writing materials, and the creation of texts.

See the Literacy-rich surroundings for more information.

Provocations for drawing and writing

Educators can use a range of different stimuli that can spark the starting time of the writing process for children.

These might include pictures, discussion questions, videos, storytelling and other experiences.

Children may cull to respond to their provocations in writing experiences, or may create their own text

Storytelling experiences tin can deed as a stimulus, and educators may employ writing frameworks (run across beneath) to spark writing/drawing ideas from children:

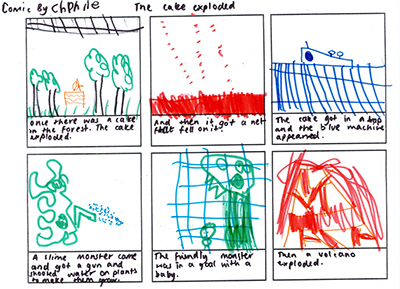

Writing frameworks

These are frameworks provided to children to help them structure their text creation.

They could include sheets with boxes and spaces for cartoon and writing.

For case:

- boxes for comic book writing

- space for a list of ingredients/materials and space of numbered steps for a procedural text (like a visual recipe or instructions)

Providing materials for independent writing

Children's writing develops farther when the learning environs supports early attempts to write. Such an environs includes attentiveness to the classroom setting and materials besides as the instruction provided. Giving children gratuitous access to writing materials and print supports their writing development. - Mayer (2007, p. 37)

Various materials can exist provided for contained writing experiences, though educators should make sure they choose materials that are safe for the child to employ without active developed supervision. Some ideas include:

- various sizes and colours of paper

- envelopes

- markers, pens and pencils

- triangular and regular crayons

- finger crayons

- letter, number and shape stamps and pads

- child safety scissors

- flake reading material for cutting and pasting

- stickers

- dry erase boards

- envelopes

- coloured masking tape

- chalk and chalkboards

- letter tracing cards

- magnetic letters and a magnetic board

- stencils

Theory to practice

Educational theorists (eastward.g. Vygotsky, 1978, Bruner, 1990) argue that children'south enjoyment and spontaneous engagement with texts is a critical goal for education of immature children. Many see this fostering of enjoyment as linked to their exposure to a rich-literacy environment (in educational settings and the home), also as fourth dimension and space to explore texts independently and with more than capable peers:

Close observations of young children learning to read suggest that they thrive on the richness and diversity of reading materials and on existence read to aloud. In fact, these early experiences feature prominently in the histories of successful readers, those children who non only know how to read but choose to read for learning and pleasure. - Neuman and Bredekamp (2000, pp. 22-23)

In this view of emergent literacy, which is aligned with Piagetian and Vygotskian philosophies, children are seen equally agile participants who accept agency to brand sense of and explore their world, using the signs, symbols, and conventions of various texts (encounter Mackenzie and Scull, 2015 for review; Rowe and Neitzel, 2010).

The means educators fix upwards contained reading experiences can help children to feel comfortable and supported to explore texts. Independent reading is thus an opportunity for emergent readers to take bureau and actively explore texts, depending on their interests and level of familiarity with how texts work, as well as the ins and outs of meaning making systems (including written language).

The ways that researchers accept viewed children's emergent writing has changed over the last xxx years:

For many decades children's first writing efforts were all but ignored by researchers… It is at present understood that children who grow up in a literate environment do not expect until school or other formal education to explore the features of writing.

They are already experimenting from a very early on age, earlier they begin to understand the alphabetic principle and despite the fact that the writing produced might not exist conventional from the perspective of an developed. - Bradford and Wyse (2010, p. 137)

This point - that children are agile participants in emergent writing experiences—has been emphasised in Mackenzie and Scull'south (2015) give-and-take of writing evolution, in which the authors note that children's cosmos of texts occurs through scaffolding from educators, as well as self-initiated writing projects. Importantly, children are supported to write (and depict) for authentic purposes, and for existent audiences.

The emergence of intentionality in writing is also an important effect, with researchers noting that children may brainstorm to engage in emergent writing with intentionality from equally early equally 12 months (Mackenzie and Scull, 2015).

Evidence of intentionality at such immature ages is significant because information technology necessitates appropriate intervention by educators congenital on positive understandings of children capabilities. - Bradford and Wyse (2010, p. 138)

For this reason, researchers have emphasised that children'southward growing emergent literacy capabilities, are dependent non merely on developmental progression, but too access to varied writing experiences (Bradford and Wyse 2010; Mackenzie & Scull, 2015)

Mayer (2007) emphasises the importance of fostering children'due south fine motor control, providing varied materials and surfaces to work with and on, and modelling how to use implements finer.

Interestingly, Rowe and Neitzels' (2010) enquiry has indicated that children with different interests, explore and brand use of emergent writing experiences differently:

Children with conceptual interests used writing to explore and record ideas on topics of personal interest. Children with procedural interests explored how writing worked and adept conventional literacy (eastward.g., writing alphabet letters).

Children with creative interests explored writing materials to generate new literacy processes and new uses for materials. Children with socially oriented interests used writing to mediate articulation social interaction and aligned their activity choices with those of other participants.

The finding that children may have different ways of interacting with texts, based on their interests, can help educators to provide a multifariousness of materials and opportunities to develop different kinds of contained writing experiences.

There is too an of import link between this pedagogy exercise (independent reading and writing), and children'south play. Children should be supported to write for real reasons, in age-appropriate ways:

Effective early childhood teachers help children experience gratuitous in their writing. They collaborate with children engaged in play in classroom action centres and innovate the idea of using writing every bit a part of children's play. Mayer (2007, pp. 37-38)

For more information, see:

- Play

- Sociodramatic play

Bear witness base

A meta-assay (Mol and Jitney, 2011) analysing the results from 99 studies, looked at the relationships between impress exposure and later reading development. The researchers found that children with frequent emergent literacy experiences (impress exposure) had stronger comprehension and decoding skills in subsequently schooling, which in turn supported them to appoint in more independent reading time.

The authors stressed the importance of creating fourth dimension and space for contained reading from an early age, to assistance create this virtuous cycle betwixt increasing exposure, proficiency, and willingness to engage in more reading:

Developing a reading habit depends not only on environmental factors such equally the availability of books at habitation but likewise on readers' linguistic communication and comprehension skills" (Mol and Bus, 2011, p. 286)

Recent enquiry has also supported the importance of providing emergent literacy experiences, including independent exploration and creation of texts, for the development of children's interest and proficiency in emergent literacy (Chang, Luo, and Wu, 2016; Hume, Lonigan, and Mcqueen, 2015).

Links to VEYLDF

- Victorian Early Years Learning and Evolution Framework (2016)

- VEYLDF Illustrative maps

Outcome 1: identity

Children develop knowledgeable and confident self-identities

- use their domicile language to construct pregnant

- develop strong foundations in both the culture and language/south of their family and the broader community without compromising their cultural identities

Consequence 2: community

Children go aware of fairness

- brainstorm to sympathize and evaluate means in which texts construct identities and create stereotypes.

Consequence iii: wellbeing

Children take increasing responsibility for their own health and physical wellbeing

- answer through movement to traditional and gimmicky music, trip the light fantastic toe and storytelling of their own and others' cultures

Outcome 5: communication

Children engage with a range of texts and get significant from these texts

- view and listen to printed, visual and multimedia texts and answer with relevant gestures, actions, comments and/or questions

- sing chant rhymes, jingles and songs

- take on roles of literacy and numeracy users in their play

- begin to understand key literacy and numeracy concepts and processes, such as the sounds of language, letter–sound relationships, concepts of print and the means that texts are structured

- explore texts from a range of different perspectives and begin to analyse the meanings

- actively utilize, engage with and share the enjoyment of language and texts in a range of ways

- recognise and engage with written and oral culturally constructed texts

Children express ideas and make pregnant using a range of media

- share the stories and symbols of their own cultures and re-enact well-known stories

- use the creative arts, such every bit drawing, painting, sculpture, drama, dance, motility, music and story-telling, to limited ideas and make meaning

Children begin to empathize how symbols and pattern systems work

- brainstorm to make connections between, and see patterns in, their feelings, ideas, words and actions, and those of others

- develop an understanding that symbols are a powerful means of communication and that ideas, thoughts and concepts tin be represented through them

- brainstorm to be aware of the relationships between oral, written and visual representations

- begin to recognise patterns and relationships and the connections between them

- listen and respond to sounds and patterns in voice communication, stories and rhyme

Children utilise data and communication technologies to admission information, investigate ideas and represent their thinking

- utilise data and advice technologies to access images and data, explore diverse perspectives and make sense of their world

- utilize information and communications technologies as tools for designing, drawing, editing, reflecting and composing

- engage with technology for fun and to make meaning.

Experience plans and videos

For ages - early communicators (birth - 18 months):

- Lots of trucks: play, reading, and extending linguistic communication (part 2)

For ages - early linguistic communication users (12 - 36 months)

- Lots of trucks: play, reading, and extending language (role 2)

For ages - language and emergent literacy learners (30 - threescore months)

- Megawombat cartoon telling

Links to learning foci and instruction practices:

- exploring and creating texts

- literacy-rich environment

- play (emergent literacy)

- reading with children (emergent literacy)

- sociodramatic play (emergent literacy)

- writing with children

References

Bradford, H., & Wyse, D. (2010). 'Writing in the early years' in D. Wyse, R. Andrews, and J. Hoffman (Eds). The Routledge international handbook of English, language and literacy educational activity. London: Routledge.

Bruner, J. (1990)Acts of meaning. Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Printing.

Chang, C. J., Luo, Y. H., & Wu, R. (2016). Origins of print concepts at home: Print referencing during joint book-reading interactions in Taiwanese mothers and children. Early on Educational activity and Evolution, 27(1), 54–73.

Knuckles, N.K. and Pearson, P.D. (2002). Effective reading practices for developing comprehension (Chapter 10), In A.E. Farstrup &Due south.J. Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2013). Better learning through structured didactics: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility.2nd Edition. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Hume, L. E., Lonigan, C. J., & Mcqueen, J. D. (2015). Children's literacy interest and its relation to parents' literacy-promoting practices. Journal of Research in Reading, 38(2), 172–193.

Mackenzie, N. M., & Scull, J. (2015) 'Writing', in South. McLeod & J. McCormack (Eds.), Introduction to speech, language and literacy. South Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Oxford University Printing.

Mayer, Grand. (2007). Research review: Emerging knowledge about emergent writing. Young Children, 62(1), 32–40.

Mol, South. East., & Omnibus, A. Grand. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early machismo. Psychological Message, 137(ii), 267-296.

Pearson, P. D.,& Gallagher, Thou. C. (1983) The instruction of reading comprehension, Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 317-344.

Rowe, D. W., and Neitzel, C. (2010). Involvement and agency in 2- and 3-year-olds' participation in emergent writing. Reading Enquiry Quarterly, 45(2), 169–195.

Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading teaching Third Ed(pp. 205-242), Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Lancaster, Fifty. (2007). Representing the means of the globe: How children nether three get-go to apply syntax in graphic signs. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 7(2), 123-154.

Neuman, South. B., and Bredekamp, S. (2000). 'Becoming a reader: A developmentally appropriate arroyo' In D. S. Strickland (Ed.) Showtime reading and writing, New York: Columbia University (pp. 22-34).

Sulzby, Eastward., Teale, West. (1985) Writing evolution in early babyhood. Educational Horizons, 64(1), 8-12

Victorian State Government Section of Education and Training (2016), Victorian early years learning and evolution framework (VEYLDF). Retrieved 3 March 2018.

Victorian Curriculum and Cess Authority (2016) Illustrative Maps from the VEYLDF to the Victorian Curriculum F–10. Retrieved iii March 2018.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Further reading

- Reading rockets: listen and learning with audiobooks

- Handwriting fonts

pattonsabighter79.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/childhood/professionals/learning/ecliteracy/emergentliteracy/Pages/independentreadingandwriting.aspx

Post a Comment for "Reading and Language Arts Foundations of Language Develop and Emergent Literacy"